Spearhand Faring and Kin-Bright

Spearhand Faring stands on its own, and can be read on its own. But Spearhand Faring does relate to Cosmic Warlord Kin-Bright, and those who’ve read Kin-Bright might spot connections here and there in the new poem. So, for anyone interested, how do the two poems compare?

Story

To take the least interesting way first, narratively speaking--in fabula rather than syuzhet, if you want--Spearhand Faring’s story happens centuries before Kin-Bright. If it happens: like CWKB, I've tried to give SF a strong sense of its own telling, hinting that it might be more legend than history. Evidence crops up in a few parts of SF to suggest that the poem itself pre-dates Tar’s fall in CWKB, and probably predates the final siege of Tar.

Tone

In tone, Spearhand Faring is I think less challenging and more comic, I hope--gently comic, not gag-driven. The end of Troilus and Criseyde has Chaucer instructing his poem to

Go, litel book, go litel myn tragedye,

Ther God thy makere yet, er that he dye,

So sende myght to make in som comedye!

Which, expansively translated, is something like ‘Go forth, little book, go forth, my little tragedy; may God yet send your writer, before he dies, the power to write some comedy’. These lines bear more weight if we remember that Chaucer, like Go Nagai, knew his Dante: comedy might mean things up to and including the Comedy.

What Chaucer in fact went on to do seems to have been his Legend of Good Women. At the start of that work, Chaucer is accosted by the God of Love and accused (accurately) of translating the Romance of the Rose and composing Troilus and Criseyde; he describes himself taking on writing the Legend in a kind of plea bargain.

CWKB is no Troilus and Criseyde, but I like the idea of following tragedy with something in a different vein.

Form

Formally, most of the narration in Spearhand Faring uses blank verse very much like that of CWKB. (I say ‘most’ because one passage briefly uses terza rima.) The metre runs similarly regular, some would say monotonous, to the pattern in CWKB, too: permitting headlessness, and inversion of the first beat, occasionally omitting offbeat at a rhetorical caesura or having offbeats either side of a rhetorical caeasura, but otherwise uniform, and sticking to blunt line-endings only. I know other, looser styles exist. I like them, too! But this style is right for these projects, because, first, it’s easier for audience that doesn’t read as much poetry and, second, if such regularity was good enough for Gower and Chaucer, it must easily be good enough for a minor poet like me.

All dialogue, meanwhile, relies on alliterating half-lines all modelled on--though not exactly matching--Sievers’s five types. This specific subspecies of alliterative verse appears in CWKB, but rarely. There, it probably represents speech that’s not only formal but also archaic.

Form stretches beyond metre and ornament, and shades into style. Compared to CWKB’s interest in high style, SF reaches far more for middle style and even, in places, low style: more relaxed vocabulary, more standard word order, with fewer moments of inversion. Speaking of low style, I want to write a little separate devlog about insults. Please hold on tight for that…

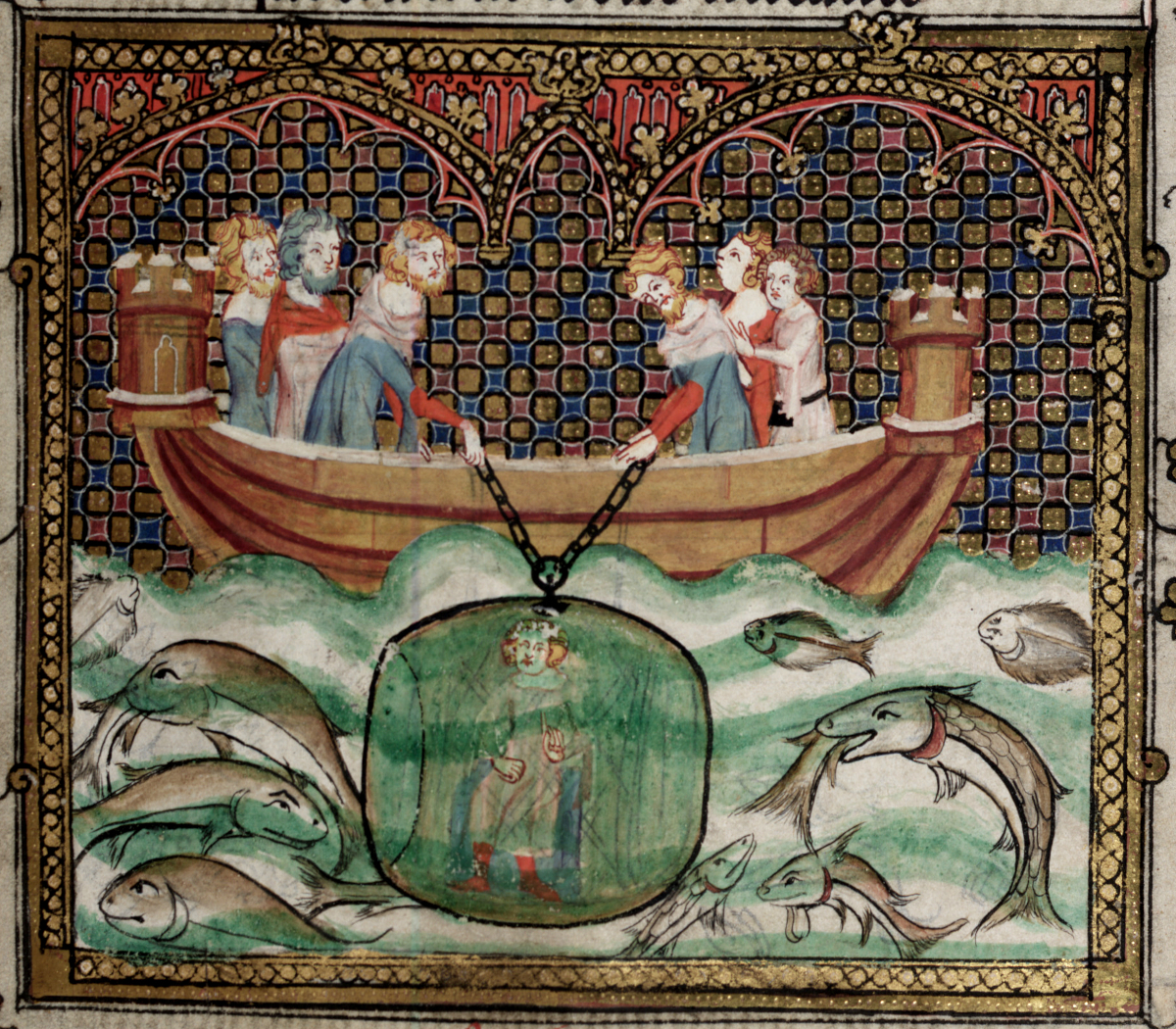

Top image: detail from Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Bodley 264, folio 50 recto, made available by the Bodleian Libraries under a CC-BY-NC 4.0 licence. See more of this manuscript in their online facsimile!

Spearhand Faring

A giant robot adventure, in verse.

| Status | In development |

| Category | Book |

| Author | Thaliarchus |

| Tags | LGBT, mecha, No AI, poetry, Romance |

| Languages | English |

| Accessibility | Color-blind friendly, High-contrast, One button |

More posts

- Word choices and form changes17 days ago

- Second draft of Spearhand Faring is complete17 days ago

- First draft of Spearhand Faring is complete77 days ago

- Release plans for Spearhand Faring99 days ago

- Brief February updateFeb 15, 2025

- A literary demakeJan 10, 2025

Leave a comment

Log in with itch.io to leave a comment.